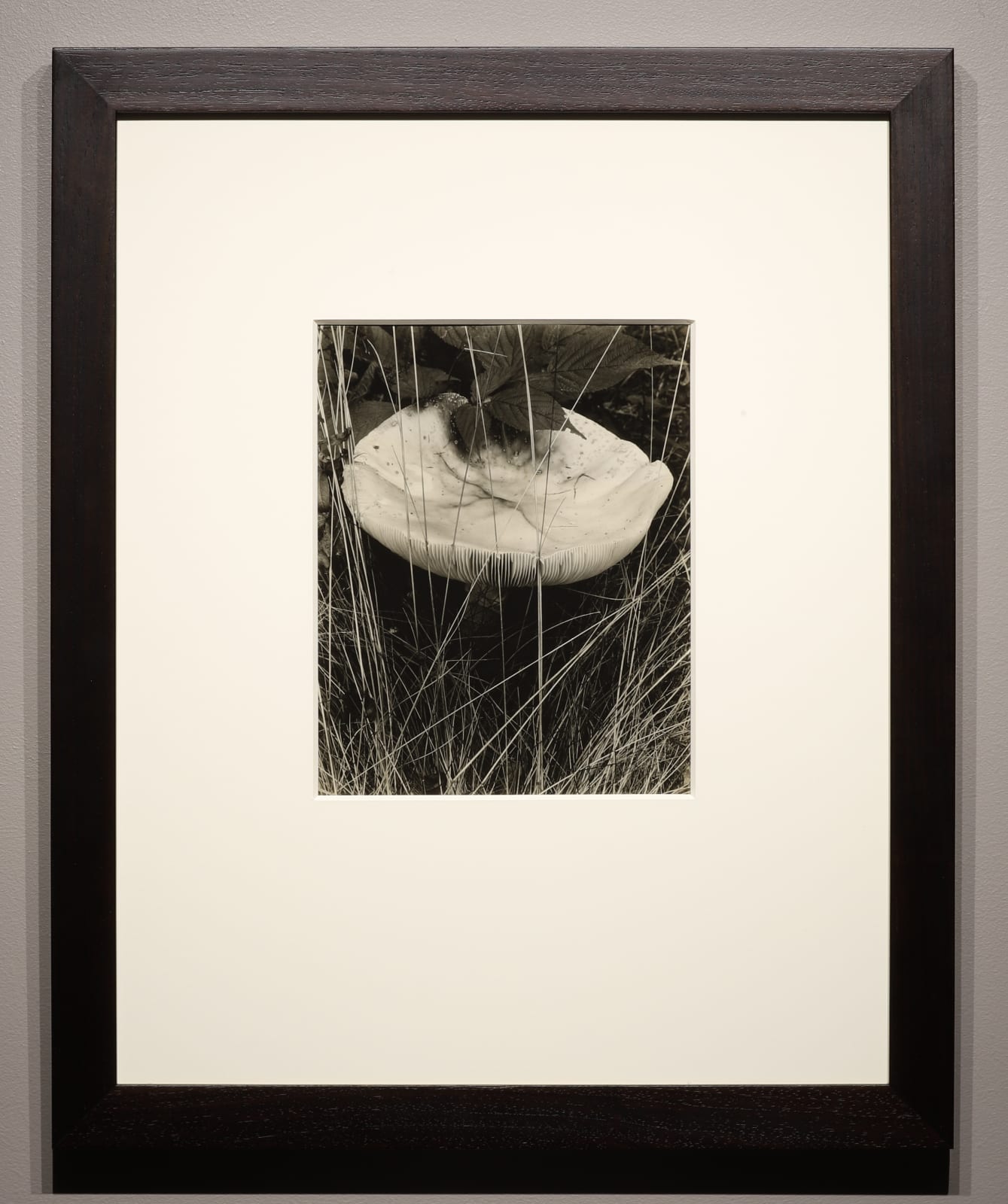

Paul Strand

Toadstool and Grasses, Georgetown, Maine, 1928

Silver Gelatin

10 x 8 in

Sold

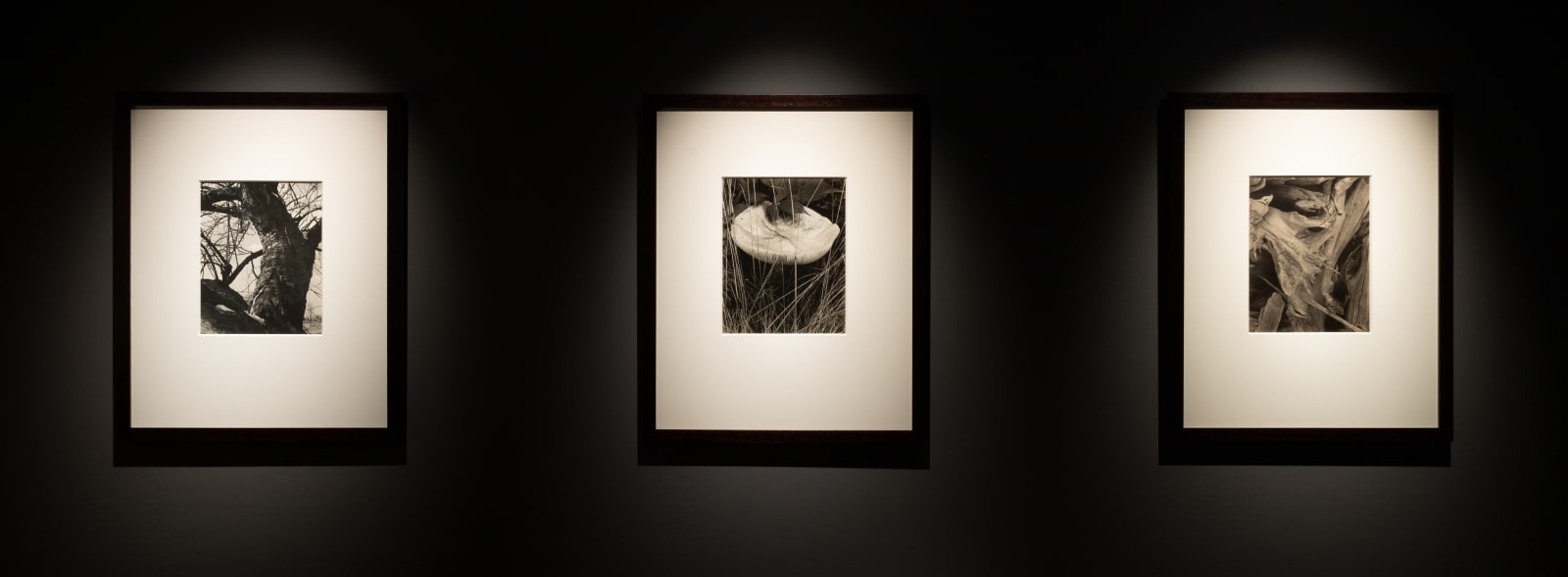

Further images

This early, untrimmed silver gelatin contact print is signed in pencil by Hazel Strand on behalf of Paul Strand. This image gained notoriety for frequent appearances at the MoMA, beginning...

This early, untrimmed silver gelatin contact print is signed in pencil by Hazel Strand on behalf of Paul Strand. This image gained notoriety for frequent appearances at the MoMA, beginning in 1940 with their exhibit “Sixty Photographs” and featured in John Szarkowski’s landmark 1973 book “Looking at Photographs,” in which this image represents Strand.

The untamed natural setting presented a new challenge for Strand, who had forged his radically formal vision in New York City, where architectural order and orchestrated movements beckoned for an aesthetic equivalent. Strand’s sculptural nature studies represent perhaps the most important inflection point in photography’s history. While modernist photographers rebelled against the medium’s prior imitation of other art forms, they still subjected photography to many of the same graphic conventions of other media. Strand’s well-known work of the 1910s flattens his subjects into 2-dimensional abstractions, which Szarkowski would call “graphic adventures.” In the late 1920s, Edward Weston and Paul Strand developed “straight photography,” not merely by stopping down the aperture and switching to glossy paper, but by recognizing the predominance of the subject over interpretive effect.

Both Weston and Strand, unwitting of the other’s work, stumbled upon the same revelation at the same time. Weston became similarly concerned with the “object quality” of his photographs in 1927-30 with his famed still life’s of shells, peppers, rocks, etc. In fact, the small aperture normally associated with the straight photography movement was a symptom of a deeper concern for dimensionality, as smaller apertures compensated for the shallow focus of macro-photography. Perhaps Szarkowski chose this image over Strand’s other nature studies because it emphasizes the object quality of the subject. With this image and others like it, photography was no longer a shortcut for drawing—it entered the third dimension, and became more than an art.

The untamed natural setting presented a new challenge for Strand, who had forged his radically formal vision in New York City, where architectural order and orchestrated movements beckoned for an aesthetic equivalent. Strand’s sculptural nature studies represent perhaps the most important inflection point in photography’s history. While modernist photographers rebelled against the medium’s prior imitation of other art forms, they still subjected photography to many of the same graphic conventions of other media. Strand’s well-known work of the 1910s flattens his subjects into 2-dimensional abstractions, which Szarkowski would call “graphic adventures.” In the late 1920s, Edward Weston and Paul Strand developed “straight photography,” not merely by stopping down the aperture and switching to glossy paper, but by recognizing the predominance of the subject over interpretive effect.

Both Weston and Strand, unwitting of the other’s work, stumbled upon the same revelation at the same time. Weston became similarly concerned with the “object quality” of his photographs in 1927-30 with his famed still life’s of shells, peppers, rocks, etc. In fact, the small aperture normally associated with the straight photography movement was a symptom of a deeper concern for dimensionality, as smaller apertures compensated for the shallow focus of macro-photography. Perhaps Szarkowski chose this image over Strand’s other nature studies because it emphasizes the object quality of the subject. With this image and others like it, photography was no longer a shortcut for drawing—it entered the third dimension, and became more than an art.